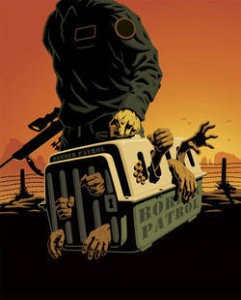

The Feds Bury Border Patrol Abuses of Immigrants, But What’s Been Unearthed Reveals a Culture of Cruelty

By Monica Alonzo, Riverfront Times, December 16, 2010

VIDEO: the fatal beat down and stun-gunning of Hernandez Rojas in this video.

Anastasio Hernandez Rojas screamed in agony as U.S. border agents rained blows on him and delivered 50,000 volts of electricity to his body over and over. “No! No! Ayuda!” the 42-year-old Mexican wailed, pleading for help in Spanish. “Ayudenme [help me]!” It was late in the evening of May 28, and his cries could be heard throughout the San Ysidro border-crossing area dividing San Diego and Tijuana.

Witnesses said that Hernandez Rojas was facedown on the ground, his arms handcuffed behind his back. Three agents were piled on top of him, one driving his knee into Hernandez Rojas’s back, another pushing his knee into the deportee’s neck. Other federal agents were kicking the father of five on each side of his body.

His chilling cries for mercy caught the attention of pedestrians on a nearby bridge that leads to Tijuana.

“Ya! Por favor! [Please, enough!] Señores! Ayudenme! Ayudenme! Por favor!” Hernandez Rojas was heard sobbing between his broken screams.

“Noooo!” he wailed. “Noooo! Dejenme! [Leave me alone!] No! Señores!”

Officials with U.S. Customs and Border Protection said after the beating that Hernandez Rojas became combative when agents removed his handcuffs.

They said he fought with agents, who used a baton to try to subdue him. When that didn’t work, they used a Taser. After agents stun-gunned him, federal officials said, he stopped breathing, and agents tried to revive him using CPR.

The border agents’ account of that night is markedly different from ones shared by witnesses who gathered around the fenced walkway used by the Border Patrol to deport immigrants to Mexico.

Humberto Navarrete, a young San Diego man, was among the witnesses who watched and listened in horror. He pulled out his cell phone and started recording the scene—never imagining he was filming the final moments of a man’s life.

The 2½-minute video he captured is grainy and dark (see it attached to this article at www.phoenixnewtimes.com), but the sounds of Hernandez Rojas’s begging for his life are clear.

Navarrete called out to two agents who had just driven up to the port of entry: “Hey! He’s not resisting. Why are you guys using excessive force on him?”

One of the new arrivals told Navarrete he didn’t know what was going on. But even as Hernandez Rojas cried miserably in the background, the agent said, “Obviously, he’s doing something. He ain’t [. . .] cooperating.”

To Navarrete, it defied logic that a Border Patrol agent who had not witnessed what was going on could conclude that these were the screams of an uncooperative immigrant.

Navarrete called out again, this time loudly to the agents pummeling Hernandez Rojas: “He’s not resisting, guys. Why are you guys pressing on him? He’s not even resisting! He’s not even resisting!”

A woman yelled in Spanish through the fence at the agents: “Leave him alone already!”

As the crowd grew increasingly uneasy, agents picked up Hernandez Rojas by his arms and hauled him to a nearby spot behind some Border Patrol trucks.

Witnesses no longer had as clear a view, but they reported that federal agents poured out of the Border Patrol station. They could tell that about 20 gathered around Hernandez Rojas, who was again facedown on the ground, still in handcuffs.

His cries, by this time, were faint.

Navarrete said he saw one of the agents gesture to his comrades, and they all stepped back. It didn’t mean that agents should lay off Hernandez Rojas. It apparently was a warning to fellow agents to step back. The agent then pulled out his stun gun and delivered electrical jolts to the restrained man.

Navarrete said he heard four, maybe six, shots from the stun gun, and saw the victim’s body convulse.

Hernandez Rojas’s whimpering could no longer be heard. His body was stone-still.

Realizing their deportee had stopped breathing, agents used CPR to try to revive him. About 10 minutes later, an ambulance arrived, and paramedics scooped up the broken man and took him to a hospital.

Eugene Iredale, a representative for the victim’s family, said medical officials who examined Hernandez Rojas believe his brain was deprived of oxygen for about eight minutes after his heart stopped. He already was brain dead when he arrived at the hospital.

About 12 hours later, doctors removed him from life support and pronounced him dead.

A deputy at the San Diego County Medical Examiner’s Office told Village Voice Media (VVM) that the cause of death was a combination of methamphetamine in his system, high blood pressure, and a heart attack.

The medical examiner noted in the autopsy report that Hernandez Rojas’s death was a homicide—a term used because he had been restrained in police custody when he died. The term does not dictate criminal guilt— that’s up to prosecutors—and no one has been charged in the killing.

When Navarrete heard later about a fatal incident involving the Border Patrol, he realized that the man who died was the one he had filmed getting beaten and stunned. He went public with his video and his recollection of that night.

That was about seven months ago, and there still are no official answers about what happened and no police reports about the incident available to the public. Guadalupe Valencia, an attorney for the dead man’s family, said he soon will file a wrongful-death lawsuit in federal court in San Diego.

Based on accounts from witnesses and from Hernandez Rojas’s brother, who was traveling with him at the time and was also detained by the Border Patrol, his family has been able to piece together some of the events leading up to his death.

Hernandez Rojas, who had lived in San Diego for 27 years, was deported to Mexico after police discovered after a traffic violation that he was living illegally in the United States. He, along with his brother, had crossed the border into California to reunite with his family. They were spotted in a rural area and rounded up by la migra.

The two were taken to a detention center in Otay Mesa, a rural border community inside San Diego’s corporate limits, and locked up in a holding cell.

Valencia said Hernandez Rojas complained at the detention center that agents were roughing up detainees. After 2½ decades in the United States, the attorney said, Hernandez Rojas knew that even undocumented aliens are constitutionally entitled to humane treatment.

Agents at the facility ordered Hernandez Rojas to get rid of a bottle of water, and he apparently dumped the water on the floor.

Agents took him to another holding cell, and while they were restraining him, one of the agents kicked him in a once-fractured ankle held together by five metal screws, according to family representative Iredale.

“As we understand it, he then wanted to make a complaint regarding his treatment,” Iredale said. “And instead of being permitted to file a complaint, or being given medical attention, [he was told he would be deported].”

Later, he was taken to the San Ysidro border crossing. But he wasn’t shuffled across the border with other undocumented immigrants. Hernandez Rojas was kept alone with agents at the crossing.

“Why was Mr. Hernandez brought alone, without other persons who were going to be returned or repatriated to Mexico, at that time of night?” Iredale said. “Why, since he was only about 100 feet [from Mexico], was he not simply turned over to Mexican authorities?”

Other questions that plague his family: Why did the aggressive treatment that the witnesses observed continue after he was restrained? Why was he moved away from where he was visible to other people? Why was he surrounded by about 20 federal agents? Why was a restrained man stunned five times?

San Diego Police Department homicide detectives conducted an investigation and turned over their findings to the U.S. Attorney’s Office in San Diego, where the case remains under investigation.

Christian Ramirez, an immigrant rights activist and member of the American Friends Service Committee, questioned the level of force agents used against Hernandez Rojas. He noted that Hernandez Rojas was in a secure area and already had been searched and processed at the Border Patrol detention center.

“It’s inconceivable that any sort of action taken by Mr. Hernandez Rojas would have led to an incident in which his life was lost,” Ramirez said at a news conference a couple of days after Hernandez Rojas’s death. “This should not happen in the United States.”

Anastasio Hernandez Rojas apparently never was allowed to file his formal complaint against Border Patrol agents at the detention center before his untimely death, but even if he was accorded that right, his complaint might have fallen into a black hole.

For months, Customs and Border Protection (which oversees the Border Patrol) repeatedly blocked attempts by VVM to find out the number and nature of complaints for excessive force or inhumane treatment filed by undocumented immigrants against border agents.

Customs and Border Protection (CBP) is part of the Department of Homeland Security, as is the Office of Civil Rights and Civil Liberties, set up to investigate complaints about any Homeland Security employee. But the latter office, while it maintains general statistics on the number of cases it handles and how many it closes, tells VVM it does not account for which cases are filed by migrants and what their specific outcomes are—which is astonishing, because CBP’s mission is dealing with immigrants.

But by perusing reports published by the civil rights office, VVM discovered that since October 2004, 103 agents or officers from Customs and Border Protection were arrested for such offenses as smuggling, money-laundering, and conspiracy.

As for prosecutions of Border Patrol agents, the closest VVM could come was a U.S. Department of Justice statement that “at least” eight agents had been prosecuted since ’04.

Seven of these cases involved the beating, sexual assault, or attempted murder of immigrants in Border Patrol custody. They do not include the still-under-investigation case in which the San Diego agents were caught on videotape savagely beating a compliant Hernandez Rojas, who later died.

As for details about agents brought up on charges, fired for misdeeds, or reprimanded, there is no sure way of discovering them—unless the rare case gets reported by an altruistic officer, winds up videotaped, or becomes part of a report by a humanitarian group—because CBP is anything but cooperative.

Infamous federal bureaucracy may be part of the problem, but the fact remains that the violent actions of border agents—who deal with a population of detainees who wind up back in Mexico, speak little or no English, and/or are too afraid or unsophisticated to complain—are cloaked in secrecy.

Even detailed information about how border agents are trained— including the kind of civil rights and weapons training they receive—is nearly impossible to come by.

It’s not just activist groups that complain about the border-protection force. Union leaders who represent Border Patrol agents suggest that agency leaders are more concerned with boosting the number—not the quality—of agents.

“As long as the Border Patrol continues to place priority on the quantity of recruits rather than the quality of recruits, corruption within the Border Patrol will rise in the future,” the National Border Patrol Council, Local 1613 posted on its website. The union represents about 1,500 non-supervisory agents and support personnel in the Border Patrol’s San Diego Sector.

One reason agents go astray appears to be that, in the federal government’s rush to add new agents in the wake of zealous calls for increased border security, CBP contends it can no longer follow its own policy of conducting polygraph examinations of potential agents.

James F. Tomsheck, assistant commissioner of CBP’s Office of Internal Affairs, told federal lawmakers during a congressional hearing in March that only about 10 percent of potential agents undergo polygraphs that, in part, help determine applicants’ motivation in seeking employment as agents. Of those who are tested, more than half are rejected as unsuitable for employment by the federal agency.

Homeland Security is adding 2,200 Border Patrol agents to help secure the nearly 7,000 miles of border that the United States shares with Mexico and Canada. Using Tomschek’s math, this means that 220 would wind up tested, with 1,980 untested agents entering federal service. But the overriding point is that nearly 1,188 of the 2,200 would be rejected if they were tested.

The polygraphs matter, Tomsheck said to lawmakers, because the tests have weeded out individuals with ties to drug cartels trying to infiltrate the agency. But he said they aren’t conducted on all applicants because the agency doesn’t have enough money to hire sufficient polygraph examiners.

Tomsheck did not address whether there would be wisdom in hiring fewer new agents to make way for sufficient polygraph examiners—so that the new agents who are hired go through at least basic agency screening.

Migrants’ stories of abuse at the hands of la migra go back decades. Border Patrol agents are accepted by Mexicans as one of the extreme dangers of illegally crossing into the United States—along with wild animals, treacherous terrain, and corrupt human smugglers hired to guide them through the desert.

Human rights organizations—including No More Deaths (No Mas Muertes), based in Tucson, Arizona; Border Angels, headquartered in San Diego; and Border Network for Human Rights, out of El Paso, Texas—have worked for decades to raise awareness of abuses that immigrants endure at the hands of border agents.

Despite their calls for reform, volunteers continue to hear stories of abuse from the men, women, and children the Border Patrol has detained.

No More Deaths volunteers documented hundreds of cases in a 2008 report, “Crossing the Line—Human Rights Abuses of Migrants in Short-Term Custody on the Arizona-Sonora Border.”

Many of the stories are incomplete because migrants are afraid to provide their full identities, and once their brief encounters with volunteers at migrant-aid stations are over, they are gone, untraceable.

Paulino arrived at the No More Deaths aid station at the Nogales, Sonora port of entry on August 5, 2006. The 29-year-old from Cancún was crying and in severe pain. He told volunteers he had traveled alone through the desert for three days before he was captured by Border Patrol agents and deported. While in custody, he said armed agents kicked him in the stomach. He said they told him they didn’t speak Spanish and refused to provide him medical attention.

At the aid station, his genitals were swollen, his urine contained blood, and he struggled to walk. The Mexican Red Cross examined him, telling him he needed surgery. But medics said he must return to Cancún for the operation. Paulino had no money for a bus ticket to get home, let alone funds for medical care. He walked away and was never heard from again.

Lola told VVM that Border Patrol agents treated her and her sister like animals after they were caught jumping over the U.S.-Mexico border fence that divides San Luis, Arizona, from San Luis, Sonora.

The sisters were loaded into the perrera (dog kennel), the immigrants’ nickname for Border Patrol transport trucks.

It was August, and the air inside the truck was stale and sweltering (desert temperatures can surpass 110 degrees in summer). A small window cut in the camper shell was closed.

Lola clung to her younger sister, despite the suffocating heat inside the aluminum oven, on a metal bench facing a few immigrant men. She said the agent driver slammed on the gas, sending the truck careening through the desert and tossing the captive immigrants into each other. There was nothing to hold on to.

She screamed at the agent to stop, slamming her hand repeatedly on the wall separating him from his day’s catch. But she said he kept tormenting them, at times speeding in tight circles through the rough terrain.

“We’re not animals!” she screamed at the agent in English, when he stopped and opened the truck’s door so a fellow agent could toss in another migrant.

The agents mocked them, she related, saying they were animals that deserved such treatment.

Human rights volunteers often hear similar stories from immigrants. Some say Border Patrol agents turn on heat in the summer or air conditioning in the winter to torture immigrants packed in the back of such trucks.

No More Deaths continues to gather accounts of abuse from recently deported immigrants in Mexico, in the hope of soon releasing another report.

Just days after Anastasio Hernandez Rojas died in agents’ custody, Border Patrol agents in El Paso shot and killed Sergio Adrian Hernandez Huereca, a Mexican teen who was among a crowd of people throwing rocks at agents.

One agent shot the unarmed 15-year-old, who reportedly had been arrested at least four times since 2008 on suspicion of human smuggling but was never charged with a crime.

A criminal history alone is no justification for killing someone who isn’t posing an immediate threat to an officer, say critics like Enrique Morones, founder of Border Angels.

Law enforcement officials in Texas are reviewing the death of 18-year-old Juan Mendez, a drug smuggler shot by a Border Patrol agent in early October. After a brief struggle, the unarmed man broke free of the agent’s hold, and the agent shot him twice.

As already stated, it is impossible to know exactly how many border agents abuse their power, and there has been no ruling as to whether these did.

Immigrant rights activists argue that this is the way U.S. Customs and Border Protection wants it—that the agency is bent on ensuring that as few abusive agents as possible are exposed publicly.

Tucson nurse Sarah Roberts sees living examples of mistreated and neglected migrants each time she travels to Mexico to provide basic medical care at migrant-aid stations, shelters, and the comedor in Nogales, Sonora.

Sometimes migrants need something stronger than her healing hands. During a September visit to Nogales, she sat inside a worn trailer with Juana, comforting her through the anguish of losing her mother, being separated from her children, and getting stuck in Nogales, more than 3,000 miles from her home and family in New York City.

A rough encounter with the Border Patrol when she was nabbed in the Sonoran Desert only aggravated her pain.

Juana had returned to Mexico about a month earlier because her mother was dying. She knew the risks of leaving her home, husband, and three-year-old son behind in the States. Even her ailing mother pleaded with her not to return.

Juana had been living in New York for nearly 20 years. She needed to see her mom one last time.

Her mother died shortly after falling into a diabetic coma. After the funeral, Juana made plans to return home. She came across the border with a small group of immigrants, but they were spotted by roving Border Patrol agents.

Juana didn’t run. She told VVM she hunkered down in fear when the agent pulled so close to her in his Chevy Suburban that she could feel heat radiating from the truck’s tires. He jumped out, grabbed her, squeezed her arm tightly, and dragged her to his transport vehicle.

“Please, you’re hurting me,” she said, which elicited no mercy from her captor.

When told this story, Border Patrol Agent Eric Cantu, spokesman for the agency’s Tucson sector, said agents have to approach every suspect as a potential threat.

There is no room, he said, for niceties in a desert where armed drug smugglers hide under the cover of darkness and where bajadores, bold enough to rob from murderous drug smugglers, roam in search of victims. There is little time to distinguish between immigrants who will submit to arrest peacefully, he said, and those who will lunge for an agent’s weapon.

“Just getting to where [agents] need to be is full of danger,” Cantu said. “And once you get there, you have a group of strangers willing to risk everything to get into the U.S.—and you’re standing in their way.”

Cantu, a former Marine with almost four years on the job, concedes that there are bad agents but that most carry out their duties with integrity:

“We’re noble men and women. And we’re dedicated to our jobs. We don’t do it to crush dreams. We don’t do it to humiliate. We do it for our country.”

Juan Carlos Diaz Romero has a much different perspective after years of tending to deported migrants who arrive with signs of abuse at the No More Deaths migrant-aid station. He routinely hears stories that immigrants were denied food, water, or medical attention while in custody.

The full-time volunteer, who lives nearby, says he suffered Border Patrol abuse when he tried to cross into Arizona.

“I’ve suffered just like they have,” he said. “I want to help, so I just stay here.”

Of the deportees he encounters, Diaz Romero says, “Many people who arrive here have been beaten, have gone days without food.

“Oh, and if they [have] run, that only made the agents angry. The [agents] beat them to punish them.”

Deportee Armando told volunteers that an agent beat him for fleeing. It happened after he had grown too tired to go on. He stopped, turned toward the agent, and threw his hands up in the air. The officer caught up, yanked Armando’s head back, and slammed his fist into the side of the immigrant’s face.

Officials deported the Michoacán native, and he later arrived at the migrant-aid station. Volunteers noted in their reports that he had scratches on his chest, was bleeding from a large gash in his hand, and looked like he had been savagely beaten.

Volunteer Sally Meisenhelder has encountered someone like Armando each time she has traveled from her New Mexico home to work at the aid station at the Nogales port of entry.

“Every day I have been at the port, I have met someone who was physically abused by Border Patrol, sometimes in a sadistic manner,” she wrote in a signed affidavit included in the “Crossing the Line” report. “The injuries I have personally seen have been fractures of feet, after being run over by vehicles, pulmonary contusions caused by beating to the chest wall, lacerations caused by being pushed down on the ground, [and] bruises and sprains.”

Sarah Roberts provided medical care to one man who told her a Border Patrol agent in Douglas, Arizona, kicked him in the head after he asked for food for a child. The man said the agent also swung his foot at a woman who asked for food. Another migrant warded off the kick intended for the woman with his hand, absorbing a blow so strong that it broke his wristwatch.

Roberts did her best to console Juana before they walked about a half-mile to the comedor.

While they ate, Roberts told the group at the soup kitchen that she was there to provide first aid and to document accounts of treatment by Border Patrol agents.

After the meal, a few went to Roberts for aspirin, a muscle rub, or something to heal the deep cuts or raw blisters on their feet. Those who needed more attention followed her to Grupo Beta, a Mexican aid station not far from the border.

In a back room, Roberts filled a small tub with water for the deportees to soak their feet. She applied medication and gave them fresh pairs of socks. Her husband helped wrap sprained ankles and handed out Girl Scout cookies and clothes.

No one Roberts saw that day volunteered that he or she had been abused by the Border Patrol. But when questioned about what they ate, the conditions of their holding cells, or how the agents spoke to them, a different picture emerged.

Some said they were given food—a few saltine crackers—and water in a dirty bucket. They said agents did not hit or manhandle them, only mocked or berated them.

Almost none of the immigrants were aware that while they were in the United States, they were entitled to the most of the same constitutional rights as Americans—rights that are supposed to protect them from mistreatment.

For example, federal law (18 USC 242) decrees that law enforcement officers cannot subject illegal immigrants to “different punishments, pains, or penalties” than those they can use legally against U.S. citizens.

Further, the Fourth Amendment affords immigrants protection from excessive and unreasonable force by law enforcement, and the Fifth Amendment decrees that they cannot be harmed while in custody or lose their liberty without due process of law.

“When we’re talking about the U.S. Constitution, about civil rights and human rights, we need to apply these to all people in this country, regardless of their immigration status. Otherwise, we’re jeopardizing our very basic constitutional rights,” said Victoria Lopez, immigrant rights advocate with the ACLU of Arizona.

“We all have a responsibility to defend these rights that we cherish, that we think are so important as Americans. If we don’t, then we erode our own system of protection.”

Despite U.S. Customs and Border Protection’s secrecy about agent training—and the notion that admittedly unfit agents are hired because polygraph examinations no longer are standard—Border Patrol officials insist that agents know the law.

They insist that agents know it is illegal to slam a baton into an immigrant’s abdomen without any legitimate law enforcement reason and that they know what reasons are legitimate.

They insist that agents know it is a violation of illegal immigrants’ constitutional rights to angrily abuse them as punishment for trying to escape.

As part of a 55-day training program to ready agents for the demands of the job, officials say, agents are schooled about the civil rights of the people they will encounter during hours of patrols across expansive stretches of borderland. But they refuse to detail how much course work is devoted to training agents about how to preserve the civil rights of immigrants.

The Border Patrol is part of Customs and Border Protection, the largest uniformed police force in the nation, with more than 40,000 agents. The Border Patrol alone already has seen its ranks double from 10,045 in fiscal year 2002 to 20,119 in ’09—with 2,200 more agents on the way. CBP’s budget nearly tripled over the past seven years—growing from $5.9 billion in fiscal year 2003 to $17.2 billion in 2010.

As CBP continues to grow, officials contend they are committed to fostering a culture of integrity among agents.

But Pedro Rios, a border activist with American Friends Service Committee, said a big part of the agency’s problem is that there is little top-down monitoring of agents’ hiring and behavior on the job.

The limited polygraph testing is a serious problem, he and other activists stress.

Tomsheck, of the CBP’s Office of Internal Affairs, admitted to lawmakers during the congressional hearing “that many of those persons hired during CBP’s hiring initiatives . . . may very well have entered into our workforce despite the fact that they were unsuitable.”

In other words, many agents responsible for protecting America’s borders would not have made it past the polygraph—which is standard for recruits at reputable law enforcement agencies across the country.

Border Patrol brochures tout starting pay for agents of up to $50,000 a year, health coverage for which the federal government picks up 75 percent of premiums, and a retirement plan. In return, the agency requires that prospective employees be U.S. citizens, have a driver’s license, and pass vision, hearing, and physical-agility tests.

Jumping into higher-paid posts requires a college degree or general work experience—including experience as seemingly unrelated to law enforcement as “customer-service representative.”

VVM could not measure how Border Patrol agents’ meager qualifications and training may have translated into abuses of immigrants.

Customs and Border Protection spokesman Steve Cribby in Washington would not provide— despite a barrage of requests——information about the number or nature of complaints filed against agents, or about how many were disciplined for mistreating immigrants.

And though agents’ jobs are defined by their encounters with illegal immigrants, Cribby said Border Patrol officials do not “track whether the source of a complaint is an illegal alien.”

Attempting to extract public information from the agency is a maddening endeavor, but once a serious instance of abuse by an agent surfaces in, say, the news media, federal officials are quick to publicly repudiate the behavior.

Assistant U.S. Attorney General Thomas Perez said in a June press release that he and federal leaders “place a great deal of trust in our federal law enforcement officials, and . . . will aggressively prosecute any officer who violates the rights of others and abuses the power they are given.”

Perez’s statement came after Border Patrol Agent Eduardo Moreno pleaded guilty in U.S. District Court in Tucson to an unprovoked attack on Alfredo Becerra Sanchez in 2006 at an immigration-processing center in Nogales, Arizona.

Moreno initially lied to investigators, telling them it was Sanchez who attacked, punched, and grabbed him. The agent said he fought back, but only in self-defense.

Unfortunately for Moreno, a surveillance camera captured the brutal beat-down, and Moreno’s actions were made public. (Moreno’s sentencing report, on VVM’s’ website, contains a detailed description of the video.)

After agents had searched Sanchez, they walked him to a fenced-in area of the Border Patrol facility where Moreno was working. Walking behind the deportee, Moreno escorted him past the enclosure to a holding cell. Along the way, he ordered Sanchez to put his hands behind his head. Although the prisoner obeyed, Moreno kicked the back of his left knee. Sanchez spun around and faced Moreno but kept his hands on the back of his head.

Sanchez stood still—even as Moreno pulled a collapsible baton from his utility belt. With a swift motion, Moreno slammed it into Sanchez’s abdomen, forcing his body to buckle forward as he stumbled backwards.

The agent moved toward Sanchez and pointed in the direction he wanted Sanchez to walk. Again, the immigrant obeyed. With his hands at his side, Sanchez walked at a normal pace in front of the agent. In the video, Sanchez appeared to turn his head slightly toward the agent as if to say something to Moreno.

“Suddenly and without physical provocation, [Moreno] strikes the victim in the back, throws him to the ground . . . stands over the victim and begins to punch him,” investigative records detail.

Sanchez starts “swinging and flailing his arms” and Moreno falls on top of him. Immediately after Moreno goes down, six or seven agents rush the scene to separate the two men and apprehend the victim.

Court records note that “from the time that [Moreno] took control of the victim to the beginning of their struggle on the ground, no other . . . agents are visible on the video.”

It is hard to believe that Sanchez didn’t cry out in pain sometime during the series of events, when Moreno kicked the back of his knee, slammed him in the stomach with a baton, struck him in the back, knocked him to the ground, or stood over him and punched him repeatedly.

Sanchez suffered a gash to the back of his head, and his face was covered in bruises. He was taken to Holy Cross Hospital in Nogales, where doctors used staples to close his head wound.

Apparently unaware that the surveillance cameras had captured his every move—or under the impression that his actions would never become public—Moreno told investigators, according to an incident report:

“[Sanchez] grabbed me and struck me behind the right ear . . . He continued to grab me, and we both fell to the floor. Upon landing on the floor, [he] sustained a cut on the back of his head.”A year later, according to court records, Moreno changed his story again. He told FBI agents that Sanchez was looking right at him with his hands in a “ready position” and refused to put them behind his head. He said he might have grabbed the man’s wrists to force him to put his hands behind his back

When Moreno finally pleaded guilty, four years later, he admitted that his assault of Sanchez was unjustified. He was sentenced to a year in prison.

“It’s very offensive to me, to the agency, when we hear about someone who abuses their authority,” said Agent Cantu, the spokesman for the agency’s Tucson Sector. “It gives the entire agency a bad name.”

He continued, “It’s unfair to judge an entire organization from the actions of one person.”

But as the previous examples and the ones that follow attest, more than “one person” within the Border Patrol has violated the public’s trust. And given the secrecy in which the actions of agents are cloaked, there is a good probability that these examples merely scratch the surface.

Luis Edward Hermosillo, a California agent, is facing sexual-assault charges for allegedly pulling over a Mexican woman with a tourist visa in June 2009, groping her breasts and genitals, and using his finger to penetrate her while her two young children were in the car.

A judge dismissed charges in 2009 against Nicholas Corbett, a Southern Arizona Border Patrol agent who shot and killed an unarmed immigrant near the border in January 2007, after jurors in two separate trials could not reach a verdict.

Brian Dick, a Tucson border agent, was sentenced in January to more than five years in prison for raping a female agent.

While his crime wasn’t directed at an immigrant, his victim shed light on the harassment agents face after reporting abuse by a fellow agent.

The Arizona Daily Star reported that the female agent told her attacker in court that she “received nonstop calls from private numbers from your buddies.” She said these callers “should be ashamed of wearing a badge and uniform.”

Her story demonstrates that if agents harassed her, one of their own, for reporting that Dick raped her, it is not a stretch to believe what human rights activists have preached for decades—agents are unlikely to report witnessing colleagues abuse immigrants.

There is no doubt that Border Patrol agents have dangerous jobs. And not all of them go home unharmed at the end of their shifts.

Jesus Albino Navarro-Montes was arrested in February 2009 in Mexico and extradited to the United States to face murder charges. Navarro-Montes allegedly ran down Agent Luis Aguilar, who later died, with a Hummer H2 in the Imperial Sand Dunes Recreation Area in California. Navarro-Montes’s case is pending.

Later that year, on July 23, a 30-year-old agent was shot and killed while on a call. Agent Robert W. Rosas Jr. was patrolling alone and had radioed spotting several individuals traveling north toward the U.S. border. Then, contact was lost.

Agents were rushing to Rosas’s location on a remote border trail east of San Diego when they heard gunshots. They found his vehicle and bullet-riddled body a few feet away.

A judge sentenced Christian Daniel Castro-Alvarez, a Mexican teenager, to 40 years in prison for Rosas’s murder.

Though stats on abused immigrants must be ferreted out by news media and activist groups, U.S. border officials are happy to release figures on assaults against Border Patrol agents.

CBP announced that, across the nation, there were 986 assaults on agents in fiscal year 2010, up from 974 the previous year. Along the Southwest border, 974 agents were assaulted in 2010, up from 958 in 2009, the agency says.

Just as immigrants endure desert conditions, including the threat of human assault, Border Patrol agents must work in the same environs, officials note. Not mentioned is that they have the advantages of citizenship, salaries, badges, and licensed weapons.

“We don’t mind tracking a group for three, four, five miles in the middle of the heat, in the middle of the cold, whatever,” Tucson Sector Agent Cantu said. “That’s what we’re about.”

“There are currently no uniform regulations. [There is] no independent oversight of the treatment of those detained,” wrote the authors of No More Deaths’ “Crossing the Line” report. “The testimonies [in the report] reveal a systematic refusal to respect the dignity of human beings and a failure to uphold human rights.”

Advocacy groups want this culture of cruelty to change. They want Customs and Border Protection to admit there is a big problem and enforce reform. They want the agency to make agents’ behavior toward immigrants transparent—stop giving the public the runaround.

On the ground level, they want agents put on notice that there will be serious repercussions if they do not inform immigrants of their rights, provide basic medical care, offer sufficient food and water, and treat them with dignity while they are detained.

Vicki B. Gaubeca, director of the ACLU’s Regional Center for Border Rights in New Mexico, said human rights organizations across the country met in September with Border Patrol leaders in Washington, D.C.

“[CBP officials] are going over their training guidelines, over their criteria for use of force,” she said, adding that the agency’s convoluted complaint system needs addressing. “Even if you had the courage to complain, you would have to figure out whom you make that complaint to.”

Pedro Rios, of the American Friends Service Committee, said his organization is part of a larger network of border groups, including the ACLU of New Mexico, talking to the federal agency about creating a border-abuse-documentation system so groups can track the information they collect on migrant abuse.

“We [could then] extract how many abuse-of-authority cases, how many shootings,” Rios said. “I do believe that it’s the government’s responsibility to have that information readily available.”

Their message is reaching members of Congress. Sort of.

During a congressional hearing on April 14 about homeland security, Representative Lucille Roybal-Allard (D-California) asked Customs and Border Patrol Commissioner Alan Bersin and ICE Assistant Secretary John Morton about abuse of illegal immigrants in Border Patrol custody.

“Can you please explain what steps you’re going to be taking to ensure that every individual in custody is treated humanely, and . . . describe what oversight [exists] to prevent abuse of detained immigrants at Border Patrol facilities. I’ve asked this question before. I’ve gotten responses. I’m told that changes are being made.

“However, I continue to hear from advocacy groups that go into these facilities and hear complaints from immigrants about their treatment. So, again, this is an area that needs attention immediately.”

Bersin gave a standard comment about the agency’s taking seriously its “commitment to humane and lawful treatment of all people taken into custody.”

And though he briefly discussed the treatment of unaccompanied minors in Border Patrol custody, he did not describe whatever oversight there may be to stop the general abuses documented by border activists.

Roybal-Allard didn’t press for an answer, and neither did anyone else.

Cantu chalks up the activists’ furor over alleged widespread mistreatment of immigrants to human nature.

“It’s almost expected, [that the immigrants] have to hate us, spread as many bad tales about us as they can,” the Tucson Sector agent said. “But what about the other stories? What about the immigrant I gave my sandwich to? And it’s not just me; agents do it many times. We give them our food and water. I wonder how often they tell that story.

“What about the man I helped pull out of a ravine? His legs were broken after he crashed his car running from us . . . What about the drug smuggler we rescued after bajadores attacked him, stole his drugs, and left him for dead in the desert?”

Human rights groups aren’t worried about agents who conduct themselves professionally. They acknowledge there are plenty of them. They want steps taken to weed out dishonest and abusive agents.

A group of about two dozen local and national organizations pushing for changes in America’s immigration policies sent a joint letter to the chairman of the U.S. House Judiciary Committee in June after the death of Hernandez Rojas at the San Diego-Tijuana border:

“A meaningful security cannot coexist with law enforcement cultures of impunity and recklessness; we urge you to use your oversight responsibilities to ensure our nation’s Customs and Border Patrol officers are adequately trained.”

Because, as the number of agents has dramatically increased along the nation’s Southwest border, the letter continues, “The training, oversight, and accountability measures for [. . .] agents have not kept pace.”

Perhaps it was this lack of training, lack of supervision that led a Border Patrol agent to square his stance, pull back his arm, and swing at Daniel—even as the immigrant walked toward the agent with his hands in the air.

The agent’s fist swooshed past Daniel’s face, narrowly missing his jaw. But the federal officer drove his elbow into the left side of the immigrant’s mouth.

Stunned by the blow, Daniel collapsed face-first on the rocky desert floor. The agent, winded and sweaty, pressed his foot on the back of Daniel’s head, quickly grabbed his hands, and cuffed his wrists tightly behind his back.

“Get up, motherfucker!” Daniel says the agent shouted. He kicked Daniel with his black leather boot.

Dianna, Daniel’s wife, stood crying next to the irate agent. She watched as her husband struggled to get to his feet without use of his arms.

“I said, ‘Get up!'” the agent barked, and then delivered another booted blow to the downed man.

Daniel groaned. He tried to move faster, inched his knees toward his chest, and finally stood. His head and body throbbed with pain, and the metallic taste of blood filled his mouth. His heart ached as he looked at his weeping wife.

The three walked toward a transport vehicle nearby. Daniel thought about the now-wasted days that he and a pack of fellow immigrants had spent walking through the desert. He regretted running when the agents arrived.

Border Patrol agents had been trailing Daniel and about 35 immigrants making their unlawful journey in the early morning of August 24. The migrants hid in the trees and brush during the day, when detection is most likely, and resumed their trek at nightfall. On the fourth day, they continued walking as the sun started to creep above the horizon. They had come so far, and many felt confident that they would make it all the way to Phoenix.

They had no way of knowing that they had been spotted hours before field agents arrived. An infrared camera mounted on a mobile-surveillance truck had sensed the heat radiating from their bodies.

The rushing headlights of Border Patrol vehicles scattered the confused and panicked immigrants.

Daniel and his wife hid in some trees, but as the agents moved closer, the couple bolted. He scampered up a rocky hillside as fast as he could. Fear pumped through his body.

The agents shouted at the migrants to stop. Daniel wasn’t sure how many officers were after them—but it wasn’t 35. Because his group was that large, he knew the agents couldn’t catch them all.

He ran without looking back until all he could hear was his own labored breathing. He glanced over his shoulder. His wife was gone.

Dianna, worn out from three nights of walking through the desert, couldn’t keep pace, and the agent had nabbed her easily.

Out of breath and out of ideas, Daniel headed back to look for his wife. Once he spotted her, he moved slowly downhill with his hands in the air, palms out, toward the fuming officer.

The agent approached and “hit me in the face,” Daniel told VVM, as he touched the side of his mouth, still bruised about 10 days later.

Daniel sat next to Dianna at the tiny soup kitchen in Nogales, Sonora.

A few people that evening shared their deportation stories. Some said they were treated well, given food and water. Many refused to share their experiences, saying only that they planned to cross the border again.

Daniel reluctantly shared his only after a couple of men pointed him out and said they had witnessed him take a beating.

“There was another man,” Daniel says. “He ran, too, and the border agent smashed him two or three times in the head with the butt of his gun.”

Sounding almost grateful, he says, “Me, I was only kicked twice.”

He says the agent treated him better as they walked to the perrera: “When I talked to him in English, he was different toward me.”

Dianna says she wasn’t injured but added that she shared a cell with a woman who had a dislocated knee.

“We told her to ask the guards for help, maybe for some ice,” Dianna said. “She told us she had, but they wouldn’t give her anything for it.”

Daniel said he never expected to be treated well by Border Patrol agents—that they are just one of the many perils immigrants face when they enter the United States illegally.

“We know things are dangerous when we cross,” Daniel said. “We just want to work. We don’t [want] anything else. We don’t have a future in Mexico.”

monica.alonzo@newtimes.com